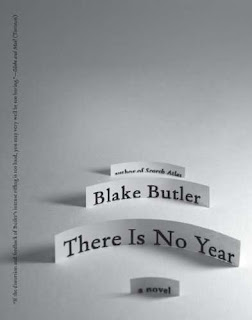

My final post of 2010 was a look at two aspects of literature--Karen Russell and Tin House--that I became fond of and looked forward to reading more of in 2011. This final post of 2011 is sort of the same. My work with Instafiction has been a joint project of discoveries. I'm now familiar with some excellent writers (David Yost and Jessica Forcier come to mind) whom I likely wouldn't have known about if it weren't for my project research. Jeremy's selections have also introduced me to some compelling literary artists, one of whom is the basis for this review. The stories of Blake Butler (The Copy Family and The Many Forms of Rain ____ Sent Upon Us In Those Days Before the Last Days) managed to stick with me long after my initial readings. In the span of a few pages, across two stories, various themes and styles pop up seemingly at random: dystopian fiction, fables, allegories, horror, and so on. I recently picked up a copy of his latest novel, There Is No Year (The Copy Family is an excerpt from this), and upon reflection, my feelings about his long-form work are contradictory. He's an undeniably talented writer, but at times a reader wouldn't be faulted for thinking that his elaborate set-ups and styles are too much when packed into a single volume.

As a personal rule, I almost never read other film or book reviews before I'm finished with my own write-ups; I want my thoughts to be solely influenced by my own critical background. However, I went through about three different review of There Is No Year, because I was sure that I was missing something. However, the thoughtful reviews explored the text exactly as I understood it. A plot summary of this novel will not give anything away, nor will it fully explain it. An unnamed family--a father, mother, and son--live in a house inhabited by copies of themselves, with minor differences.

"The copy family would not go away. The father worked himself into a state, shouting curse words, splaying arms. He went out to the car and got a softball bat he'd used for pickup games in college--he's not once had a hit, though he'd been beaned more times than he could count on all the hands in all the houses on the street where his house stood--he could often still remember how the ball felt each time, banging fast into his muscle--how his chest would scrunch then expand--how he sometimes seemed not there at all. The father stood at the window with the weapon. He threatened legal action. He spoke in unintended rhyme. He said his own name to the copy father. The copy father seemed to have more hair than him (Butler 13-14)."

After awhile, the mother takes it upon herself to kill off the copy family. After this is done, the three family members become isolated in their own problems and surreal happenings. The father's job is unsatisfying, and he notices the streets to his job growing to the point that his commute takes up most of his day. The mother falls into a state of madness, and discovers an egg-like object that produces intense orgasms. The son seems to suffer more than anyone. There are hints to a previous (and possibly ongoing illness); He develops a relationship with a mysterious girl in his school; and his online communications veer from mystical to creepy. Throughout the novel, the family tries unsuccessfully to sell the house, even with offers of exorbitant cash. Mysterious visitors drop in, and the house has its own life force, with hallways and movements and ominous objects discovered by the family. Plague-like occurrences become almost normal: ants burrow through the house and the son, and the mailbox becomes infested with caterpillars.

On their own, these plot points would seem like the basis for a compelling horror novel. There are moments in There Is No Year that definitely constitute horror:

"The black creation that'd been seated on the neighbor's house's front lawn all this time had by now spread around the structure, further on. It had covered over the old doors and windows with new doors and windows, such as the one the son had come to stand in front of, sopping wet. The son did not see the swelling structure. The son did not see the street, nor his own house there beyond the pavement--the same house they'd lived in all these years, they did not know they'd never moved. The son couldn't see much for all the glaring--even if he had seen, even if he wanted, his house would not be there. The son felt sure that he'd arrived (Butler 243)."

There are also elements that hint to a kind of surreal science fiction:

"At sudden nodules in the network, the father found holes where he could see back into the house--the living room, the upstairs hallway--the walls there had been painted over black--in some rooms orange or yellow--screaming neon--though here the vents went so thin he could not see them, not even partly, just his arms. Some rooms had been filled with dirt or smoke or foaming. Some rooms were full of skin--other families, people, bodies--smushed. One hole into one very far room was the exact same size as his eye--through the hole he could see another small eye seeing. His eye. Light (Butler 263)."

Through all of this, the initial confusion becomes accepted. The reader is not supposed to "get" what "the novel is about." When I read a book, I have a tendency to underline multiple passages and take a lot of notes in the margins. Going back through There Is No Year, I realized that my markings were nearly nonexistent. There is such a wealth of detail and activity, but unless a certain section is repeated or expanded, the novel works as a progression of what the family experiences. I eventually gave up on trying to find active threads or connections and let myself get lost in the atmospheres. Keeping with the personal contradictions in my reading habits, Butler has created a work that is its own contradiction: it's a blend of minimalism (no names, no mentions of a specific city, and stark details) and extravagant forms. The pages are dark shades of grey, there are occasional photos that may or may not reflect the immediate text, and some of the chapters are poetic stanzas or drawn out over multiple pages. The overall atmosphere calls attention to creativity in all its forms. It would be too easy and tempting to make a reference to "the medium is the message," but it seems that Butler intentionally takes this to the extremes.

There Is No Year won't work for everyone; I can only imagine how divided people can be over this novel, especially since I felt personally divided--there are multiple passages of terrific writing and atmosphere, yet I occasionally found it to be lacking or unsuccessful in its execution. However, I still have the utmost respect for Butler's creativity, and more than once, I found specific chapters that would work exceptionally well as their own short stories, thus turning back to what started my first appreciation for his work. While not every novel needs a tidy conclusion, the ending of the book is far too succinct. Readers can draw their own conclusions and attempt to create hypotheses to why the family experienced what they did, but for the most part, there's a too-familiar pattern of compelling details that draw the reader in, yet never get mentioned again. Butler is a masterful storyteller who is intentionally audacious in his forms and philosophies, but there's an unnerving wonder as to whether he built the work up so much that it collapses under its own weight. Some of the jacket blurbs hint to Butler creating a new form of American fiction. There's definitely a potential for that, but in due time. There Is No Year has definite hints to further brilliance, but its problems are just scattered enough that breathless praise is too much, too soon. I love his writing, and for now I appreciate his shorter pieces. There Is No Year certainly has its merits, but tries to go in too many directions. I don't want Butler to reign in his styles, but this work could maintained its aura and questions and could have been even better with just a bit more condensing.

Work Cited:

Butler, Blake. There Is No Year. Copyright 2011 by Blake Butler.